Cold Feet, Warm Waters: Russia’s Strategic Retreat

When Sir Halford Mackinder devised his Heartland-Rimland theory, the rulers of Russia had long cherished dreams of becoming a hybrid power that would encompass the straits of both the Heartland and Rimland. While Russia is the world’s largest country by land area, much of its coastline lies in the Arctic Ocean, which is frozen for most of the year. This geographic constraint has historically limited Russia’s ability to maintain a year-round blue-water navy, efficiently export goods through maritime trade, or establish overseas influence through naval projection, thereby hindering its achievement of strategic autonomy. To overcome this, Russia has consistently sought access to warm-water ports, coastal outlets that do not freeze in winter and remain operational year-round. “Access to warm seas” became a longstanding geopolitical goal for any Russian ruler. Now, however, this centuries-old policy is under threat as Russia finds itself increasingly squeezed out of the warm waters it once sought to dominate.

Peter the Great sought access to the Baltic Sea to modernize Russia and open it to Europe. He founded St. Petersburg as a “window to the West.” Catherine the Great expanded southward to gain access to the Black Sea via wars against the Ottoman Empire. She annexed Crimea in 1783, incorporating the warm-water port of Sevastopol. During the Great Game of the 19th century, Russian expansion into Central Asia aimed to reach the Persian Gulf or the Indian Ocean, bringing it into conflict with British interests in South Asia.

During the Soviet Period, Russia’s goal looked almost achieved. However, most of its access in practice was maintained through proxies or basing agreements in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Nevertheless, through such arrangements, Moscow secured access to strategic maritime chokepoints.

When a nation pursues a particular objective over generations, that goal inevitably becomes ingrained in its national identity and is reflected in its foreign policy. This is why Vladimir Putin’s revisionist agenda, centered on territorial expansion, should come as no surprise.

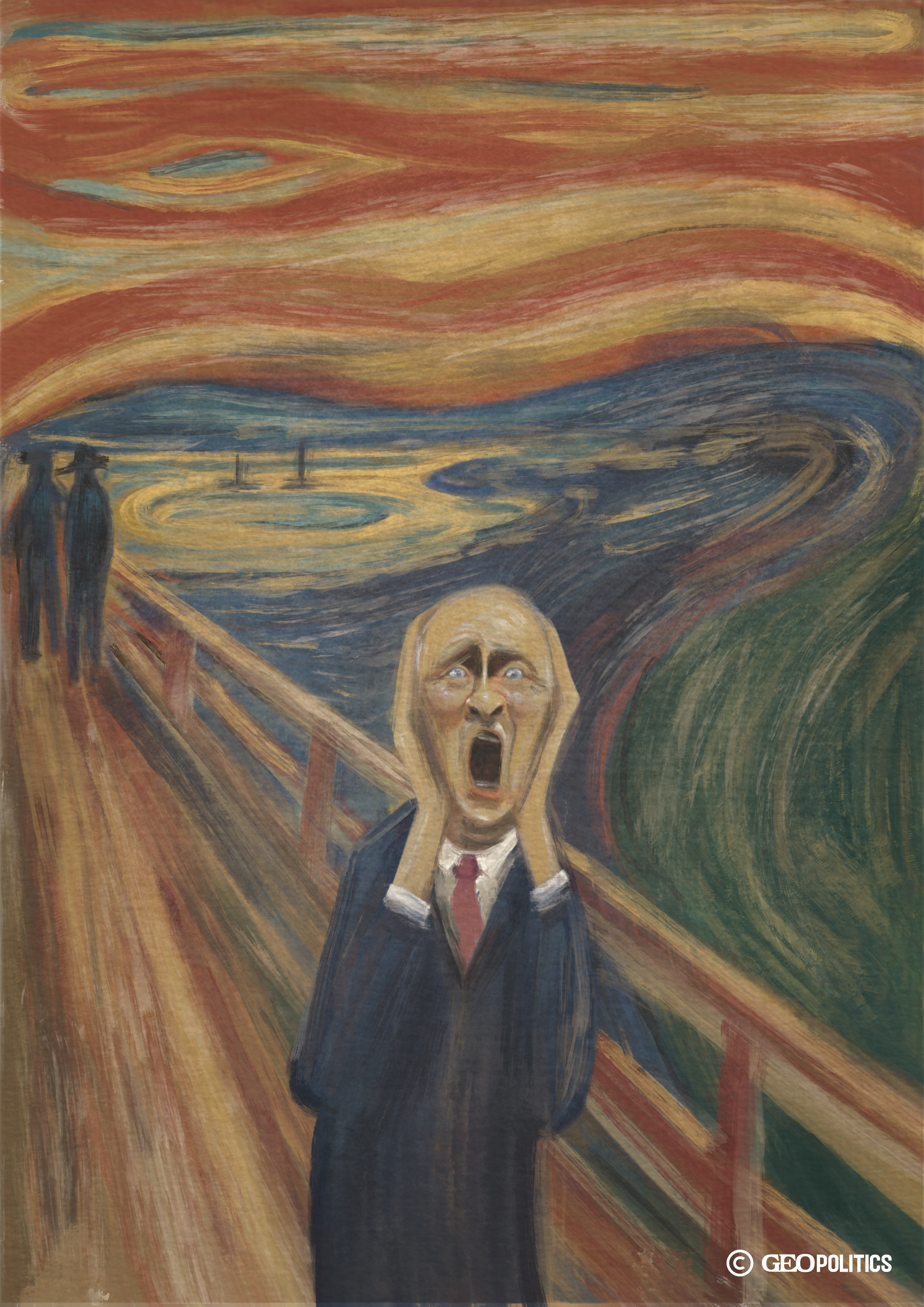

When a nation pursues a particular objective over generations, that goal inevitably becomes ingrained in its national identity and is reflected in its foreign policy. This is why Vladimir Putin’s revisionist agenda, centered on territorial expansion, should come as no surprise. His statement that the collapse of the USSR was the greatest tragedy of the 20th century is not just rhetoric; it reflects a deeply held worldview that, regrettably, the West has failed to interpret as a serious threat. From the wars against the Ottomans to interventions in Crimea and Syria, Moscow has consistently followed a strategic pattern that still shapes the Kremlin’s geopolitical mindset today.

Evolution of Expansionist Russia

It all began in 2008 with Georgia. While Estonia had earlier endured the first state-sponsored cyberattack, that confrontation remained virtual - no casualties, no physical destruction. Russia’s invasion of Georgia marked a new and dangerous precedent. By openly occupying two of Georgia’s regions, Moscow deployed a familiar yet archaic narrative: the need to protect Russian speakers from genocide or ethnic cleansing. This echoed imperial justifications dating back to Catherine the Great, who waged war in Crimea under the pretext of defending Christian populations.

With this act, Russia effectively shattered the post-Cold War world order, the so-called Pax Americana. Yet, the response from the self-proclaimed guardians of that order bore no resemblance to the global outcry over Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Instead of decisive action, the West offered half-measures: weak sanctions, tough talk, and little else to alter Putin’s course.

In September of 2015, when Russia officially intervened in the Syrian civil war on the side of Bashar Al Assad, it became obvious that Russian plans far exceeded its immediate neighborhood or the “Near Abroad” as the Russians call the post-Soviet space. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and a war in Donbas were still in Russia’s backyard; however, Syria was a different region and on a different scale. Such intervention resulted in the re-emergence of the Russian naval base in the Mediterranean port of Tartus and the airbase in Latakia. Lack of a proper response further emboldened Russia and its soldiers, disguised as “private military contractors,” who emerged in other parts of the world, mainly in Africa. By 2020, according to the German daily newspaper Bild, citing a leaked secret German Foreign Ministry report, Russia was building military bases in six African countries, with a primary focus on Sudan, as it sits on the strategic Red Sea waterway.

Due to the invasion of Georgia, Ukraine, and military expansion in the Middle East and Africa, Russia significantly extended its projection of power on the Black and Mediterranean Seas as well as on other maritime routes in the south.

In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. After fierce resistance, the port city of Mariupol, almost completely ruined and devastated due to continuous and indiscriminate bombardments, fell into the hands of invaders. Russia was quick to declare the annexation of “new territories,” indicating that the historically “normal” practice of territorial expansion was back on the agenda. Due to the invasion of Georgia, Ukraine, and military expansion in the Middle East and Africa, Russia significantly extended its projection of power on the Black and Mediterranean Seas as well as on other maritime routes in the south. In parallel, Russia exposed its ambitions in the area of growing importance – the Arctic.

These military advancements were complemented by Russia's growing role in various newly established regional and global institutions such as the Eurasian Economic Union, BRICS, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. All aimed to undermine the West's dominance in international affairs.

All seems to be working well for Russia and its expansionist ambitions, until just recently.

Beginning of the End

Russia’s prolonged war against Ukraine—marked by limited or costly gains and mounting Western sanctions—pushed Moscow to seek new partners, a kind of “coalition of the willing” as a means to defy sanctions and provide lifelines. In reality, countries like China, India, Iran, the UAE, Türkiye, and North Korea saw not an alliance, but an opportunity to exploit Russia’s vulnerability. Russian exports were snapped up at deep discounts while sanctioned imports arrived at inflated prices.

Facing heavy battlefield losses and outdated weaponry, Russia turned to Iran and North Korea for drones, ammunition, and military hardware. It leaned heavily upon China for electronics and other goods while selling oil and gas to China and India at bargain rates, offset only by the soaring costs of maintaining its sanction-evading shadow fleet.

Domestically, unpopular conscription laws triggered a wave of emigration among young professionals and skilled workers, deepening the country’s brain drain. The Russian economy shifted increasingly toward wartime production, with defense spending ballooning to historic levels. As the Ukrainian front stagnates and the illusion of Russian military and economic supremacy wanes, Moscow finds itself trapped in a vortex that is not only draining its resources but also steadily eroding its global role and influence.

The October 7 attack by Hamas on the Israeli state unleashed a chain reaction, causing tectonic changes in the Middle East and globally, leaving Russia on the side of the losers. The war against Hamas resulted in a quick war against Hezbollah in Lebanon, and its demise as a formidable military force triggered a dramatic fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria. Losing its important proxies, Iran became the next target, and a 12-day war left it without top military leadership, top nuclear scientists, and viable nuclear enrichment capabilities. The widely advertised strategic partnership with Russia did very little (if anything at all) for regimes in Syria and Iran once all hell broke loose. Notorious Russian air defense systems were quickly neutralized, leaving the skies exposed for Israeli and American warplanes. Any form of potential re-arrangement of the Middle East basically leaves no room for Russia to play.

Russia’s declaratory “friend” – Türkiye, on the other hand, drastically increased its posture in the Middle East, becoming one of the major powerbrokers, often filling the void left by Russia.

The bad news did not end for Russia in the greater Middle East. Disenchanted Armenia, long seen as Russia’s major partner in the Caucasus, saw no value in a strategic partnership with Moscow during the war with Azerbaijan in 2023 over Nagorno-Karabakh and quickly and effectively turned toward the West. More than that, putting aside historic grievances toward the Ottoman Empire and its successor, Türkiye, a previously unthinkable rapprochement between the two countries became a reality. Nikol Pashinyan’s recent visit to Ankara is a testament to this. As a “cherry on the top,” rumors are circulating that Azerbaijan and Türkiye have all but decided to build a military airbase on Azerbaijani soil, crossing Russia’s theoretical red lines of having new NATO bases at its borders.

Azerbaijan-Russia relations reached a historic nadir in late 2024 and early 2025. On 25 December 2024, Azerbaijan Airlines Flight 8243, a civilian Embraer jet from Baku to Grozny, was downed by a Russian Pantsir-S surface-to-air missile, killing 38 people, according to multiple investigations and intercepted military communications. President Ilham Aliyev publicly accused Russia of a cover-up and demanded transparency and accountability. Although Putin issued a limited apology, the damage was done, triggering Azerbaijan to suspend cultural exchanges, cancel diplomatic visits, and withdraw accredited Russian journalists.

The spat escalated further when, in June 2025, Russian authorities detained several ethnic Azerbaijanis in cities like Yekaterinburg, with at least two reportedly dying in custody under suspicious circumstances. Allegations of abuse and ethnically motivated persecution prompted Baku to launch a formal criminal investigation. In a clear act of retaliation, Azerbaijani authorities arrested multiple Russian nationals on charges ranging from cybercrime to drug trafficking, signaling that these were not ordinary law enforcement actions but a direct response to Moscow’s conduct. What began as a tragic military incident had now devolved into a full-blown diplomatic rift marked by tit-for-tat arrests, mutual recriminations, and the sharpest deterioration in Azerbaijan-Russia relations in decades.

The eastern frontier has also become a strategic quagmire for Moscow. China has overtaken Russia as the dominant economic player in Central Asia.

The eastern frontier has also become a strategic quagmire for Moscow. China has overtaken Russia as the dominant economic player in Central Asia, finalizing massive infrastructure and trade agreements, such as the long-delayed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway and expanding dry ports at Khorgos, that bypass Russian territory altogether. Simultaneously, Türkiye and Azerbaijan are advancing the Zangezur Corridor, a seamless land bridge between the Turkic republics that sidelines Russia from regional transit and erodes its geopolitical relevance. Once culturally anchored to Moscow, Central Asian states like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are now dismantling Russian linguistic and media influence, forging stronger ties with China, the Gulf, and Western powers. Russia, meanwhile, finds itself reduced to selling oil and gas at heavily discounted rates and failing to secure key deals such as the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline. Even its once-dominant security role is fading as troop drawdowns and China’s increased military assistance to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan shrink the Kremlin’s strategic footprint. In effect, Russia is being squeezed out, economically, politically, and militarily, from a region it once considered its uncontested sphere of influence.

New Realities for Russia

The Middle East, the South Caucasus, and Central Asia, which were once seen as pivotal points in Russia’s regional power projection, are now showing signs of Moscow’s retrenchment. Moscow’s declining role is not a temporary reallocation of resources but a structural setback with long-term consequences for Russia’s global position.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has left fewer resources available for overseas operations. Western sanctions have limited Russia’s ability to project power. Export controls on semiconductors, avionics, and energy technologies have hampered the maintenance and modernization of military equipment. Russia’s arms exports—once a key tool of influence—have declined sharply due to both capacity constraints and reputational damage.

Russia’s traditional partners are increasingly hedging or drifting away. In the Middle East, countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and even Syria are diversifying their foreign relations. The Abraham Accords, Israeli-Gulf rapprochement, and China's role in normalization talks between Arab states and Iran have reduced the need for a Russian balancer. Türkiye‘s assertive policy and China's economic diplomacy have also reduced Russia's role.

Russia's image as a protector of allies has been severely damaged. This loss of credibility extends beyond allies. Neutral and even formerly aligned states are increasingly cautious about Russia’s capacity to deliver on promises, forcing them to seek alternative patrons or pursue greater self-reliance.

Russia's relationship with Israel has also deteriorated. Although the two had previously coordinated closely in Syria, Russia’s growing ties with Iran and its criticism of Israeli policies in Gaza have created tensions. After a 12-day war between Israel and Iran, and Russia’s pro-Iranian position, there is very little appetite in Israel to take Russia seriously.

Meanwhile, countries like Egypt and the UAE, which had significant defense cooperation with Russia, are pivoting toward Western partners or enhancing self-sufficiency in response to uncertainty about Russian reliability.

As a result, Russia is gradually shifting from a position of decisive influence to a more reactive and defensive stance. In diplomatic terms, it is no longer commanding the spotlight but increasingly relegated to the margins. Although some analysts once framed Russia’s resurgence as a sign of an emerging multipolar world, its current retreat exposes just how fragile that narrative was. What is taking shape instead is a fragmented global landscape where regional powers pursue their own agendas with little coordination or collective vision. Russia’s diminishing role is also weakening the cohesion of alternative alliances like BRICS and the CSTO, which now struggle to project unity or strategic relevance.

Russia’s loss of influence in these regions reduces its ability to bargain in broader geopolitical contexts. Its marginalization in Syria or the Caucasus limits its relevance in energy diplomacy, counterterrorism, or refugee policy. Moreover, Western countries now have a freer hand to engage these regions without navigating Russian veto power. President Trump’s initial suggestion to restart talks with Russia about all geopolitical issues is now history, with Russian propagandists openly attacking Trump for yielding to the “deep state.”

Over the last several decades, NATO and the EU have become more assertive in the West than ever before. The enlargement of both organizations, expedited by the Russian invasion, is yet another inevitable consequence that Russia sought to prevent. With Finland and Sweden in NATO and European unity over Ukrainian defense assistance, the Russian dream of a disunited and detached Europe is far from materializing, even with the unpredictable policy of the new Washington administration.

Bottom line – Russia’s attempt to reassert its global posture and secure access to warm waters is rapidly unraveling, threatening the viability of the entire expansionist project, if not the integrity of Russia itself.

Georgia, the Misfitting Piece

Against the backdrop of seismic geopolitical shifts that alienate Russia from its surrounding regions, Georgia stands out, not as a rising regional partner, but as a state deliberately detaching itself from its future and embracing Moscow. Once the pride of the post-Soviet democratic wave, Georgia has regressed into an unrecognizable shell, led by a government that seems hostile to its own people’s aspirations and dangerously indifferent to its strategic surroundings. The ruling Georgian Dream party has not only turned its back on the country’s Euro-Atlantic path, it has also begun actively mocking it, pushing conspiracy theories about the West as a “deep state” and accusing Europe and the U.S. of plotting wars on Georgian soil. What was once a nation that inspired the region now parades through its towns with banners of Ayatollah Khamenei and praises for Trump, bizarrely stitched together in anti-Western rallies that defy ideological coherence. Ask “What is wrong with Georgia?” and the answer today is devastatingly simple: everything.

Ivanishvili is not just a silent partner—he is, today, Russia’s only true ally on the Black Sea. And he holds that position not by force or blackmail, but by choice.

This turn is not happening in a vacuum. While Russia is being systematically edged out of the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Black Sea, hemmed in by Turkish infrastructure, Chinese investment, and Western rebalancing, it has found one oddly loyal outpost: the regime of Bidzina Ivanishvili. As Moscow’s ships are denied access to Mediterranean ports and its leverage in the South Caucasus withers, Georgia offers a rare strategic win for the Kremlin: a government that voluntarily echoes Russian propaganda, blocks EU integration, adopts Russian laws, and persecutes civil society with Soviet-style tactics. Ivanishvili is not just a silent partner—he is, today, Russia’s only true ally on the Black Sea. And he holds that position not by force or blackmail, but by choice.

Meanwhile, the region around Georgia is undergoing rapid transformation. Armenia has broken decisively with Moscow, aligning itself with the West and seeking reconciliation with Türkiye. Azerbaijan and Türkiye are building a strategic corridor that links the Caspian to Europe, bypassing Russia entirely. Central Asia is being pulled into China’s orbit with trade, infrastructure, and even military cooperation flowing eastward. In this shifting landscape, Georgia should have been the West’s anchor in the region—politically stable, economically open, strategically located. Instead, it is morphing into a pariah state, out of sync with both its neighbors and its citizens.

Georgia today resembles an awkward, ill-shaped puzzle piece—one that no longer fits into the Western-led picture of regional security, prosperity, and cooperation. The Georgian people have not changed: their overwhelming support for EU membership, their protests against authoritarian drift, and their defiance in the face of repression prove this.

Georgia today resembles an awkward, ill-shaped puzzle piece—one that no longer fits into the Western-led picture of regional security, prosperity, and cooperation. The Georgian people have not changed: their overwhelming support for EU membership, their protests against authoritarian drift, and their defiance in the face of repression prove this. What has changed is the positioning of the ruling regime, which views loyalty to Russia as a survival strategy. But the geopolitical puzzle will be completed—with or without Georgia. The only question is when (and whether) the Georgian people and the West will finally act, with clarity and courage, to ensure that Georgia is shaped by its own democratic will, rather than by the influence of others. That window is still open, but not for long.