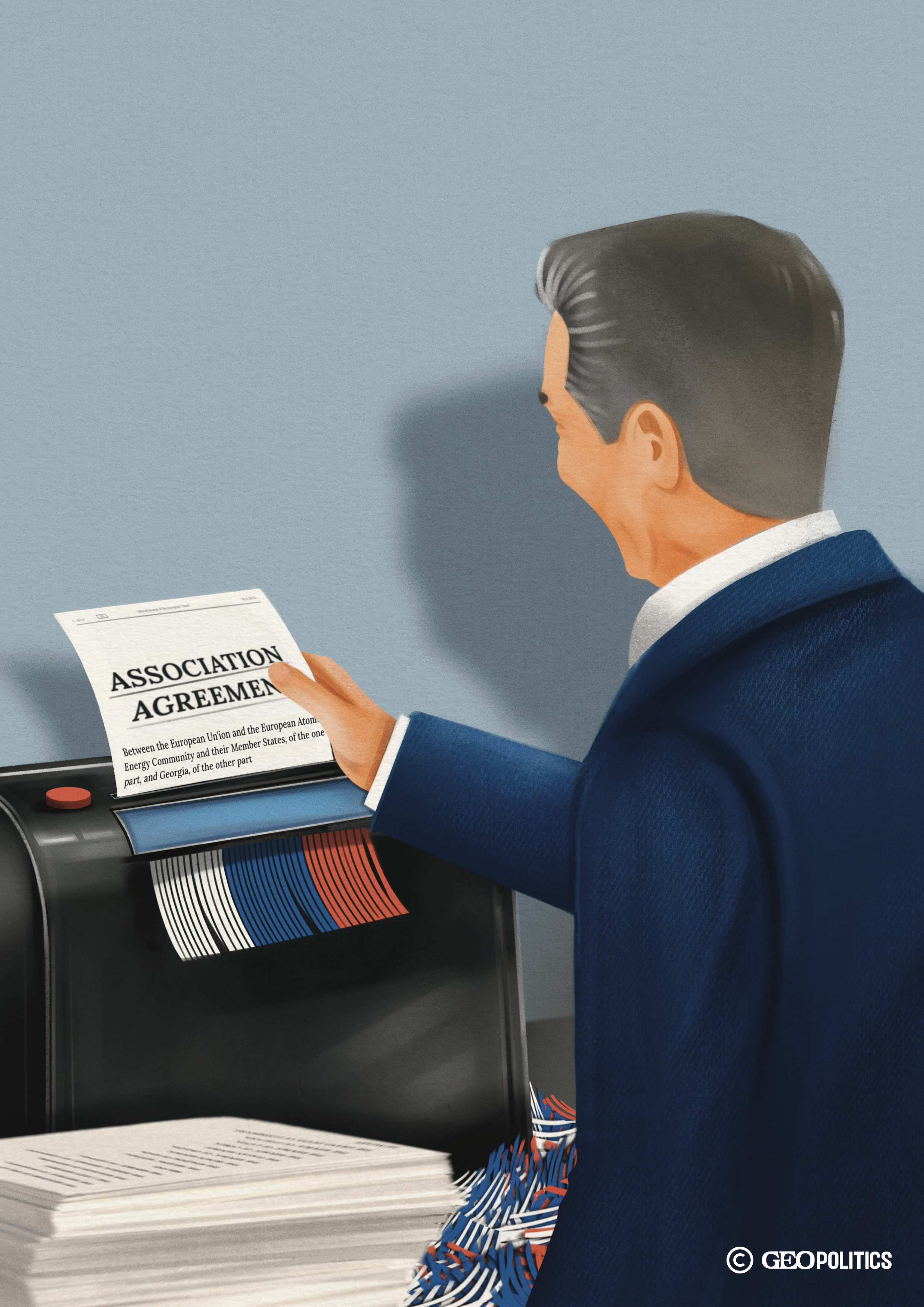

The EU-Georgia Association Agreement: The Unused Lever

When the European Council conferred candidate status on Georgia in December 2023, Brussels hoped that the gesture, symbolically closing the gap with Moldova and Ukraine and showing respect for the Georgian people’s European identity, would prompt the Georgian Dream government to return to the European track. Instead, it triggered what is now certainly a deliberate skid away from the Union.

Barely six months later, the Georgian Dream rammed through its “foreign agents” law, shrugged off street protests with mass arrests, street beatings, intimidation campaigns, and powerful propaganda, before engineering a rigged October 2024 election that the European Parliament would brand “neither free nor fair.” Irakli Kobakhidze’s subsequent declaration that accession talks would stay off the agenda until 2028 was more than a tactical pause; it was an open breach of Article 78 of Georgia’s own constitution, which obliges every state body to pursue EU integration.

Over the past six months, Georgia has undergone a full-speed authoritarian transformation. The ruling party has launched an all-out assault on democratic institutions, opposition parties, civil society, and the free press. Peaceful protesters and activists have been beaten and jailed, opposition leaders prosecuted or imprisoned, and citizens and journalists fined for Facebook posts critical of the government.

Over the past six months, Georgia has undergone a full-speed authoritarian transformation. The ruling party has launched an all-out assault on democratic institutions, opposition parties, civil society, and the free press. Peaceful protesters and activists have been beaten and jailed, opposition leaders prosecuted or imprisoned, and citizens and journalists fined for Facebook posts critical of the government. The courts have been closed off from public scrutiny, and “a parliamentary commission” is now preparing to ban opposition parties altogether. Most alarmingly, the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) has come into force, compelling civil society organizations to register as “foreign agents,” disclose sensitive data, and face criminal prosecution, thereby paving the way for raids and arrests of NGO leaders. The anti-corruption bureau is even considering dubbing active NGOs as having political aims, which would entail confiscation of all donor-provided funds. This coordinated campaign of repression, anti-Western propaganda, and legislative control stands in direct violation of Georgia’s EU Association Agreement (AA) and its constitutional commitment to European integration.

Notably, during his November 2024 address, Kobakhidze promised that Georgia "will continue to implement the obligations based on the association agenda and the free trade agreement, as foreseen by the government’s program,” aiming to fulfill 90% of these obligations by 2028. In reality, with the anti-democratic steps taken only in 2025, the ruling party violated a number of articles of the Association Agreement.

The Preamble and Article 350 of the Association Agreement pledge the parties to nurture civil society, while Chapter 20 (Articles 369-371) obliges the government to facilitate, rather than criminalize, NGO cooperation financed by the EU. By branding EU-funded organizations “foreign agents,” the Georgian Dream openly discriminates against the EU-based legal persons and their Georgian partners in violation of Article 79’s national-treatment and MFN guarantees. The new constraints also contravene Articles 80 and 81, which promise progressive liberalization and legal predictability, and they also impede the cross-border service delivery and presence of service providers protected by Articles 91-92.

More importantly, Article 2 of the EU-Georgia Association Agreement clearly states that “respect for the democratic principles, human rights, and fundamental freedoms … shall form the basis of the domestic and external policies of the Parties and constitutes an essential element of this Agreement.”

This raises the question: if Georgia is in such a stark violation of its Association Agreement obligations, will the EU take action against the blatant breaches by the Georgian Dream, or will it continue to refrain from using the Association Agreement as a lever?

How (and When) Can Brussels Pull the Brake?

The review of the Association Agreement was one of the issues discussed at the Foreign Affairs Council on 23 June 2025. Before that, the EU Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos indicated the possibility of reviewing a free trade deal with Georgia. In reality, a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) is an integral part of the Association Agreement. Legally and politically, the DCFTA is embedded within the broader treaty framework—it forms Title IV (Trade and Trade-related Matters) of the Association Agreement, covering Articles 25 to 249, with its enforcement and dispute-settlement mechanisms linked directly to the agreement’s general provisions.

Therefore, reviewing the DCFTA necessarily entails reviewing the Association Agreement itself, as any suspension, amendment, or arbitration related to the trade chapter must follow the procedures and legal channels set out in the agreement. While the EU could theoretically suspend trade preferences (such as tariff reductions or market access) without terminating the entire Association Agreement, such a move would still constitute partial suspension under the treaty and not a separate or isolated action. In practice, initiating a DCFTA review sends a clear political signal that the EU is questioning Georgia’s overall compliance with the Association Agreement, particularly its core principles outlined in Article 2.

A complete freeze of the entire Association Agreement would require unanimity among the EU member states. Article 218 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) regulates the suspension of the agreements signed between the European Union and third parties. The article states that the Council, on a proposal from the Commission or the HRVP, shall adopt a decision suspending the application of an agreement. However, it also states that the Council shall act unanimously regarding the Association Agreements and contracts which are candidates for EU accession. Lacking a consensus in place, primarily due to Budapest's support for the Georgian Dream, the European Union is less likely to be able to suspend the Association Agreement with Georgia. Moreover, many in Brussels and the EU capitals (as well as in Tbilisi) think that such a scenario might give the Georgian Dream a pretext to further push Georgia away from the European Union rather than bringing about any positive changes.

Lessons from the Precedents

Precedents matter. In 2022, the Council froze EUR 6.3 billion in cohesion funds to Hungary under the Rule of Law Conditionality Regulation due to endemic corruption and judicial interference. Cambodia lost a third of its “Everything but Arms” trade preferences in 2020 after dismantling its political opposition, and Sri Lanka saw its GSP+ status revoked in 2010 following an EU investigation into allegations of war crimes. None of these cases involved full treaty suspension; yet, every one leveraged market access to defend human rights clauses.

The most relevant example is unfolding right now with Israel. Spurred first by Spain and Ireland and then formalized by a Dutch-led bloc of 17 member states, the Council asked High Representative Kaja Kallas on 20 May 2025 to review Israel’s compliance with Article 2 of its Association Agreement because it blockaded Gaza. The External Action Service produced its analysis in barely a month, and a “structured dialogue” with Israel is now underway; if talks fail, the EU could suspend tariff preferences by qualified majority, setting a live precedent for Georgia.

It is true that the EU has historically been reluctant to invoke human rights clauses for suspending international agreements.

It is true that the EU has historically been reluctant to invoke human rights clauses for suspending international agreements. According to the European Parliament report, most such suspensions have been made under the Cotonou Partnership Agreement—a comprehensive treaty between the European Union and African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries. Article 96 of that agreement (detailing the procedure for opening consultations and adopting appropriate measures) has been applied 17 times since 2000, following violent government overthrows, election irregularities, or human rights violations. While in some of these cases, EU action did not extend beyond opening consultations, in others, the EU took appropriate measures, such as reducing development aid and suspending certain forms of cooperation. There is no case where the EU has activated the non-execution clause, leading to the suspension or termination of the agreement on the grounds of the 'essential elements' clause being breached. In 2011, the EU partially suspended the application of the 1977 Cooperation Agreement with Syria, invoking the United Nations Charter, as that agreement did not contain a human rights clause.

First Things First

Brussels is not powerless. But it needs to be strategic.

Brussels is not powerless. But it needs to be strategic. The European Union can sidestep the absence of consensus by halting the engagement with Georgia in selected policy fields, such as trade arrangements or various programs. Unlike imposing personal sanctions, these parts do not require unanimity from the EU side.

But before jumping to the punishment, the EU should first initiate the Association Agreement review through the process spearheaded by the European Commission and the EEAS. Process matters. Through the launch of the process, the EU can send a signal that the Georgian Dream is about to lose something big—trade preferences.

The Association Agreement is a binding treaty. Article 420 obliges both sides to “take any general or specific measures required” to reach the pact’s objectives, while Articles 257-259 allow either party to suspend DCFTA concessions.

To act effectively, the EU should operationalize the dispute settlement procedures built into the Association Agreement. First, the Commission should submit a formal request for consultations under Article 246, citing Georgia’s foreign agent law and other restrictive laws as a breach of Articles 76, 78-85, and 88-92, which guarantee the enabling environment for civil society, non-discrimination, and transparency in policymaking. The EU could also refer to Article 2 of the Association Agreement and its breach, citing numerous non-democratic steps taken by the Georgian Dream. These consultations must begin within 30 days and even faster in cases of urgency.

If the Georgian side refuses to modify or repeal the laws, the EU can escalate under Article 248 by requesting the establishment of an independent arbitration panel.

If the Georgian side refuses to modify or repeal the laws, the EU can escalate under Article 248 by requesting the establishment of an independent arbitration panel. Within 120 to 150 days, that panel would issue a binding ruling, but it can certainly act sooner. If the verdict confirms that Georgia is in violation, and Tbilisi still fails to act within a 50-day grace period, the EU can invoke Articles 257-259 to suspend selected benefits of the DCFTA, which is part of the Association Agreement framework.

Yes, the timeframes outlined in the Association Agreement raise eyebrows, since many in Georgia and in the EU feel that we are running out of time. The pace of tyrannical laws, actions, and rhetoric is indeed unmatched. However, the EU must understand that reviewing the agreement is not about the final punishment, but more about the process. Obviously, this legal challenge must be accompanied by other concrete steps, including the continuation of the support for civil society, sanctioning Georgian Dream officials, and conditioning a prospect of the EU supported regional infrastructure projects (such as under the Black Sea electricity cable or the digital link between the EU and Georgia) on the reversal of the autocracy in Georgia.

The EU should clearly frame the process as a defense of its legal order, not an act of political pressure. The EU should also be ready to counter imminent Georgian Dream propaganda that the EU is “punishing Georgians.”

This legal route can provide Brussels with a powerful and rules-based toolset to defend European values without appearing politically vindictive. But to succeed, the EU must also prepare a coherent inter-institutional effort. DG TRADE, the EEAS, the EU Delegation in Georgia, and the Legal Service should jointly develop the case and designate arbitrators. Simultaneously, strong political messaging is essential: the EU should clearly frame the process as a defense of its legal order, not an act of political pressure. The EU should also be ready to counter imminent Georgian Dream propaganda that the EU is “punishing Georgians.” Pro-active campaigning by the EU delegation in Georgia and the frequent statements by the Commission spokesmen, HRVP, and the Member States can help in this regard.

Brussels should be prepared to take further action if the Georgian Dream refuses to comply with the adverse ruling. In that case, the EU should be ready to coordinate parallel responses: working with the international financial institutions to suspend loans and financial aid, to further sanction Georgian Dream leaders, including the MPs who stand behind every piece of restrictive legislation, and even review Georgia’s EU candidacy status and visa liberalization (regularly discussed by Brussels and the EU Member States) for the architects and backers of the oligarchic regime. The message must be clear – the Georgian Dream cannot violate the legal commitments it undertook with the EU and still expect to benefit from them. The EU must not punish the Georgian people, but must go to great lengths to punish the regime architects and enablers.

If Brussels were to trigger such a review with Georgia, it would establish two immediate pressure points. First, the DCFTA underpins more than 21 percent of Georgia’s total exports; suspending even a slice of tariff-free access would hit Georgian Dream-linked business elites who have so far skirted personal sanctions. Second, the review itself would provide a structured, time-limited process with clear benchmarks, replacing the current pattern of open-ended “concern” statements that the ruling party has learned to ignore.

In the long run, Georgia’s drift from Brussels is not irreversible, but time is no longer on the EU’s side.

In the long run, Georgia’s drift from Brussels is not irreversible, but time is no longer on the EU’s side. The Israel review shows that Article 2 clauses can be activated swiftly when a critical mass of member states demands it. Cases of Cambodia and Hungary demonstrate that partial suspensions of economic benefits bite hardest when tied to concrete remedial steps. If Brussels wants to preserve its relevance in Georgia—and “vindicate” the 80 percent of Georgians who still wave EU flags in the streets—it must decide whether to move from carrots to consequences before Kobakhidze’s self-declared 2028 horizon becomes a self-fulfilling exit.