Why Crimea Matters to Georgia

Since President Donald Trump’s return to the White House, there has been a strong push to end the war in Ukraine and establish parameters for sustainable peace. The way this war ends will also define the emerging world order, shaping foundational principles of interstate behavior and global governance. Moscow has always made it clear that it is not fighting for Ukraine itself, but to end global Western dominance that has “humiliated” Russia and denied it its rightful place among the world’s great powers. In Putin’s words, “the crisis in Ukraine is neither a territorial conflict nor an attempt to restore regional balance. The question is much broader and more fundamental. We are talking about the principles upon which the new world order will be based.”

Moscow has always made it clear that it is not fighting for Ukraine itself, but to end global Western dominance that has “humiliated” Russia and denied it its rightful place among the world’s great powers.

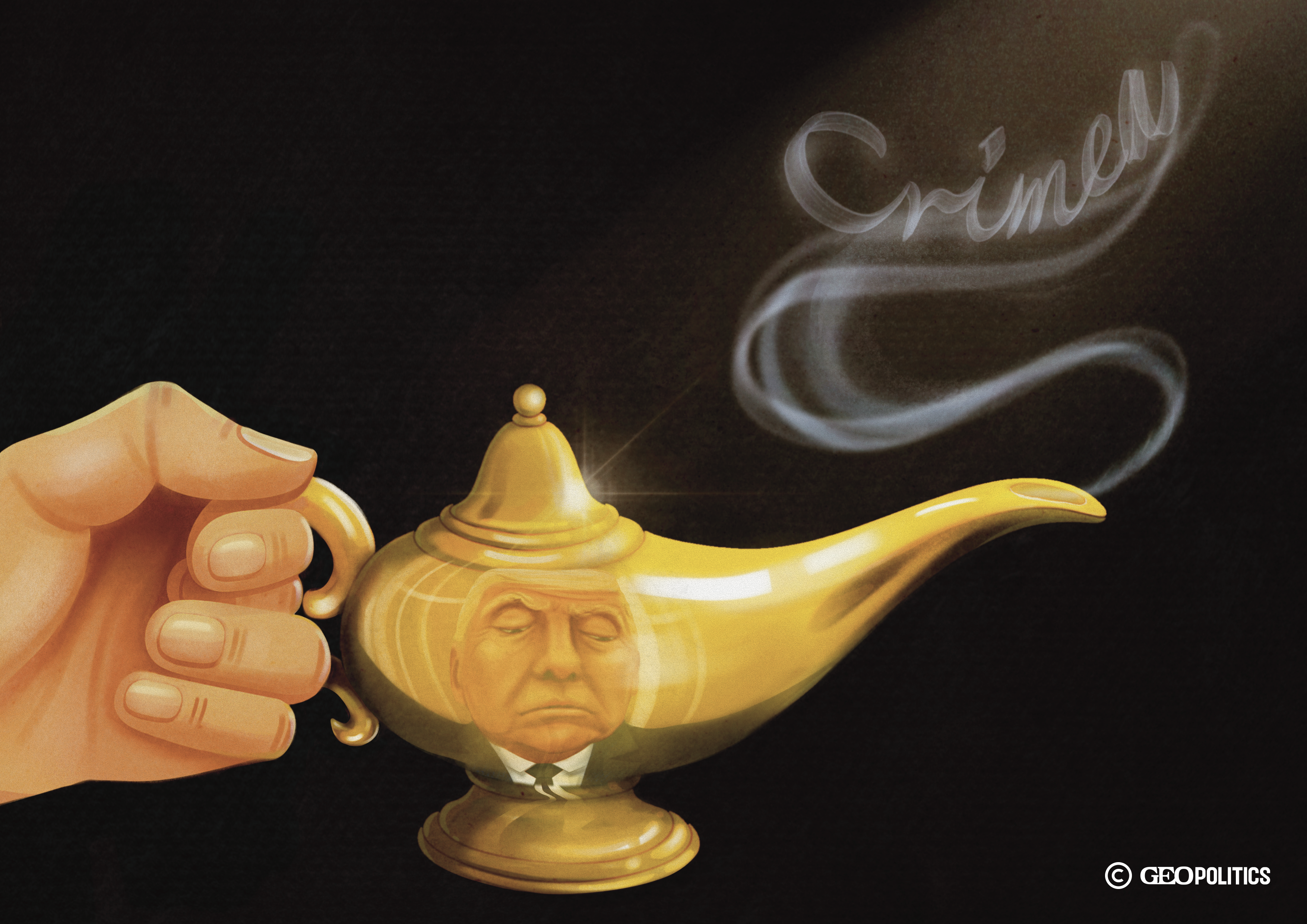

In what appears to be an attempt to satisfy Russia’s ambitions and seek compromise, Trump has raised the possibility of recognizing Crimea as Russian. This would mark a dramatic departure from longstanding U.S. policy, exemplified by the 1932 Stimson Doctrine, which established the refusal to recognize territorial changes achieved by force. The doctrine was also applied to the Baltic States after their forced incorporation into the Soviet Union in 1940, an act the United States never recognized throughout the Cold War. Recognizing Crimea would deal a severe blow to the international legal order, effectively legitimizing territorial revisionism based on selective, self-serving historical narratives.

While Trump’s proposal may be intended to end the bloodshed, it also reveals a worldview that accepts—if not embraces—the right of great powers to carve out spheres of influence and redraw borders by force. It reflects a deeply transactional approach to international affairs where norms are expendable and contested histories become tools to justify aggression. By suggesting that Putin can “have” Crimea, Trump normalizes his own rhetorical claims over places like Canada, Greenland, or Panama. While no one expects the U.S. to pursue wars of territorial conquest, this stance risks encouraging greater adventurism among other powers less constrained by domestic accountability or international obligations.

Whether or not Crimea remains de jure part of Ukraine, even if de facto occupied by Russia, would directly affect Georgia’s chances of restoring its territorial integrity.

Georgia exemplifies how a seemingly pragmatic approach to resolving one dispute—while disregarding international law—can backfire elsewhere, setting a dangerous precedent. Whether or not Crimea remains de jure part of Ukraine, even if de facto occupied by Russia, would directly affect Georgia’s chances of restoring its territorial integrity. Accepting Russia’s claims would signal an end to the multilateral conflict settlement process, firmly placing occupied Abkhazia under Russian control and posing a long-term security threat to the rest of Georgia. The balance of power in the Black Sea would shift again in Russia’s favor, enabling Moscow to reassert influence throughout the South Caucasus, including Georgia. Most importantly, it would signal the primacy of power over norms, leaving smaller states like Georgia more vulnerable and less secure. Ultimately, it could hasten the unravelling of Georgian democracy. If the global order that once constrained great powers and promoted democracy collapses, it will be replaced by one more hospitable to autocracies, shielding them from external scrutiny and enabling domestic abuses.

Norms, Precedents, and International Law

Georgia has been one of the beneficiaries of the post-Cold War international order; that is, the one that emerged with the Western victory in the Cold War and which was underpinned by U.S. power. The so-called liberal international order was based upon a strong normative consensus about the behavior of states within and amongst each other. It allowed for small states to achieve independence and claim sovereign equality, taming the predatory instincts of great powers through international law. It championed democratic governance and respect for human rights as the foundation not only for domestic stability but also international security.

Thanks to the spread of these principles, the violation of Georgia’s territorial integrity has not been accepted or recognized, preserving at least a faint hope for a negotiated solution. Russia’s efforts to secure recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia have failed, largely due to the mobilization of Georgia’s Western partners—one of Tbilisi’s biggest diplomatic victories. Georgia has also received EU candidate status, which, if pursued in good faith, could have offered an opportunity to engage the EU more directly in conflict resolution efforts.

International norms alone do not prevent wars, but they do provide the criteria by which state behavior can be judged and by which we distinguish between just wars and unjust wars.

International norms alone do not prevent wars, but they do provide the criteria by which state behavior can be judged and by which we distinguish between just wars and unjust wars. Norms that are upheld by major powers have a stabilizing impact on the international system, reducing incentives for adventurism and creating a framework for identifying aggression, prosecuting war crimes, and deterring future violations. To abandon these norms in the name of multipolarity or to draw moral equivalence between those who protect and abuse human rights is to open the door to a wave of instability, conflict, and authoritarianism.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the principle of uti possidetis juris was adopted to recognize new states within their existing administrative boundaries, aiming to prevent territorial disputes and ensure a smoother post-Soviet transition. Russia, while formally adhering to the principle, never fully respected its application to its former imperial subjects. Beginning from the 1990s, Moscow encouraged separatist tendencies among Russian speakers in the Baltic States and autonomous regions in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to apply pressure and maintain influence. In 2008, Russia openly violated the principle of the inviolability of internationally recognized borders in the case of Georgia, recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states. With the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow once again rejected the principle of recognizing Soviet successor states within their administrative boundaries, making a bogus historical claim that Crimea has always been Russian and that its transfer to Ukraine was a mistake reflecting national weakness. In both Georgia and Crimea, Moscow has invoked Russia’s responsibility to protect citizens and ethnic kin abroad, referencing the Kosovo precedent to justify its actions.

Kosovo, however, represents a clear case of remedial secession, grounded in international law and backed by international oversight. Violation of territorial integrity is permissible only in cases where there is compelling evidence of gross and systematic oppression. The absence of such evidence is the crucial distinction between the cases of Abkhazia and Crimea and internationally recognized instances of secession, such as Kosovo. In no case, however, is annexation by another state permitted as a remedy for the violation of human rights. Purposefully ignoring these important distinctions, Russians have repeatedly argued that there is no distinction between Kosovo, on the one hand, and Abkhazia or Crimea, on the other. In the words of Putin: “Our Western colleagues created this precedent with their own hands in a very similar situation when they agreed that the unilateral separation of Kosovo from Serbia – exactly what Crimea is doing now – was legitimate and did not require permission from the country’s central authorities.” He further questioned: How come Russians in Crimea are not allowed to exercise the same rights as Albanians in Kosovo?

While Kosovo cannot serve as justification for unilaterally violating another state’s territorial integrity, recognizing the illegal seizure of Crimea risks doing exactly that. For Georgia—a state with territorially concentrated ethnic minorities—such a precedent could encourage further fragmentation as respect for international law erodes. All state borders are, to some extent, arbitrary, shaped by historical contingencies, conflict, and compromise. Allowing their revision by force, especially on the basis of unsubstantiated historical claims or unilateral aggression, invites instability across Eastern Europe and beyond.

Power Imbalance in the Black Sea

Despite historical and symbolic references, Crimea’s primary importance to Russia lies in its value as a military base and launchpad to project power across the Black Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Africa. Russia annexed Crimea in response to Ukraine’s signing of the Association Agreement (AA) with the EU, fearing the loss of Ukraine to the West—and, with it, the strategic Black Sea fleet base. This demonstrates Moscow’s willingness to act not only against potential NATO expansion in areas which it deems its sphere of influence, but also in retaliation for closer ties with the EU. Accepting Russia’s territorial revanchism against an independent state strips it of the right to make sovereign choices and emboldens Moscow to pressure others, including Georgia. Tbilisi seems to have taken the cue and unilaterally abandoned the decade-long ambition of European integration in the name of preserving peace.

A stronger Russian position in the Black Sea would further distance Georgia from its European and Euro-Atlantic integration prospects. With Crimea firmly under Russian control, Moscow would dominate the longest coastline, including Abkhazia, where it is building a new naval base. This would leave Georgia highly vulnerable to Russia’s conventional and grey zone operations, undermining national and economic security and damaging its potential as a reliable transit corridor. The Russian naval base in Ochamchire, for example, directly threatens the strategic Anaklia deep-sea port, a key project along the East-West Middle Corridor transit route.

The Middle Corridor connects Europe primarily via two key routes: the Black Sea (by sea) and Türkiye (by land). If Russia asserts dominance in the Black Sea or repositions its fleet there, it could pose a significant security threat to these connectivity projects. Control of the Black Sea is crucial for Russia to maintain influence over Europe-East Asia transit, disrupt the logistical and supply chain integration of its neighbors with Europe, and undermine connectivity initiatives that bypass Russia.

If Russia were to capture Odesa, it would dominate Black Sea grain and energy trade routes, influence global food security, and project power toward the Global South.

Moreover, Russian control of Crimea poses a continuous threat to Ukraine’s remaining coastline, especially the vital port city of Odesa. If Russia were to capture Odesa, it would dominate Black Sea grain and energy trade routes, influence global food security, and project power toward the Global South. This would significantly bolster Russia’s position in the Black Sea, expanding its instruments of influence and creating new dependencies. Handing Crimea to Russia, therefore, would not be a symbolic concession but rather a strategic gift to a revisionist power set to expand its global geopolitical ambitions and upend the rules of the international order.

No-Rules-Based International Order

Conceding Crimea as part of peace talks without Ukraine’s explicit consent appears to rest on two main fallacies. First, it assumes Russia’s objectives are primarily territorial and that a land-for-peace approach could deliver lasting stability. Yet, Putin has repeatedly stated that his goals are broader and non-territorial: to destroy Ukraine as an independent nation or subjugate it entirely. In doing so, Russia asserts its claim to a sphere of influence and seeks great power status as a rule-maker in a new multipolar world. If allowed to succeed in Ukraine, nothing would stop Russia from pursuing similar strategies against other neighbors, including Georgia.

Crimea could become a highly destabilizing precedent, influencing the international system for decades to come. International law, by establishing norms, constrains states in their aggressive pursuit of naked self-interest and reduces the instances of negative precedents.

The second fallacy assumes that a ‘solution’ applied to one case, justified by context-sensitive expediency, will not be applied or repeated elsewhere. Yet, if there is one enduring principle in international relations, it is the power of precedent. Russia’s use of the Kosovo precedent, even if entirely in bad faith, is a case in point. As noted earlier, Crimea could become a highly destabilizing precedent, influencing the international system for decades to come. International law, by establishing norms, constrains states in their aggressive pursuit of naked self-interest and reduces the instances of negative precedents. This is precisely why global revisionist powers such as Russia seek to rewrite the rules to impose the least possible constraints on their behavior.

Russia’s vision of the global order assumes that some states are more sovereign than others and that their choices should be constrained by great power interests. It emphasizes non-intervention in internal affairs as a core principle, asserting the equal legitimacy of all forms of domestic governance. This is an international order where support for democratic forces is delegitimized, regime security outweighs human security, and autocracies feel safer than democracies. Georgia is emerging as a clear example of how a self-serving ruling elite can adapt to this new no-rules order—dismantling democratic institutions, jailing opponents, and pulling the country back into Russia’s orbit.

Georgian democracy is endangered not so much by Russia’s strategic gains but by the retreat of the U.S. from supporting democracies and breaking from its tradition of legitimizing the results of aggression. As Ivan Krastev wrote in the Financial Times in May: “The historical period that started with the unification of Germany ends with the partition of Ukraine.” By making an exception out of Crimea, Trump risks normalizing land grabs justified by half-truths and strategic expediency. What is framed as a singular concession could become a template for future violations of sovereignty. Georgia should be worried and working with European partners to avoid such a scenario. However, its ruling elite is more preoccupied by its own survival and sees the erosion of normative constraints as serving its own narrow political interests.