The New Security Environment in NATO’s Eastern Flank

Differences of Perception

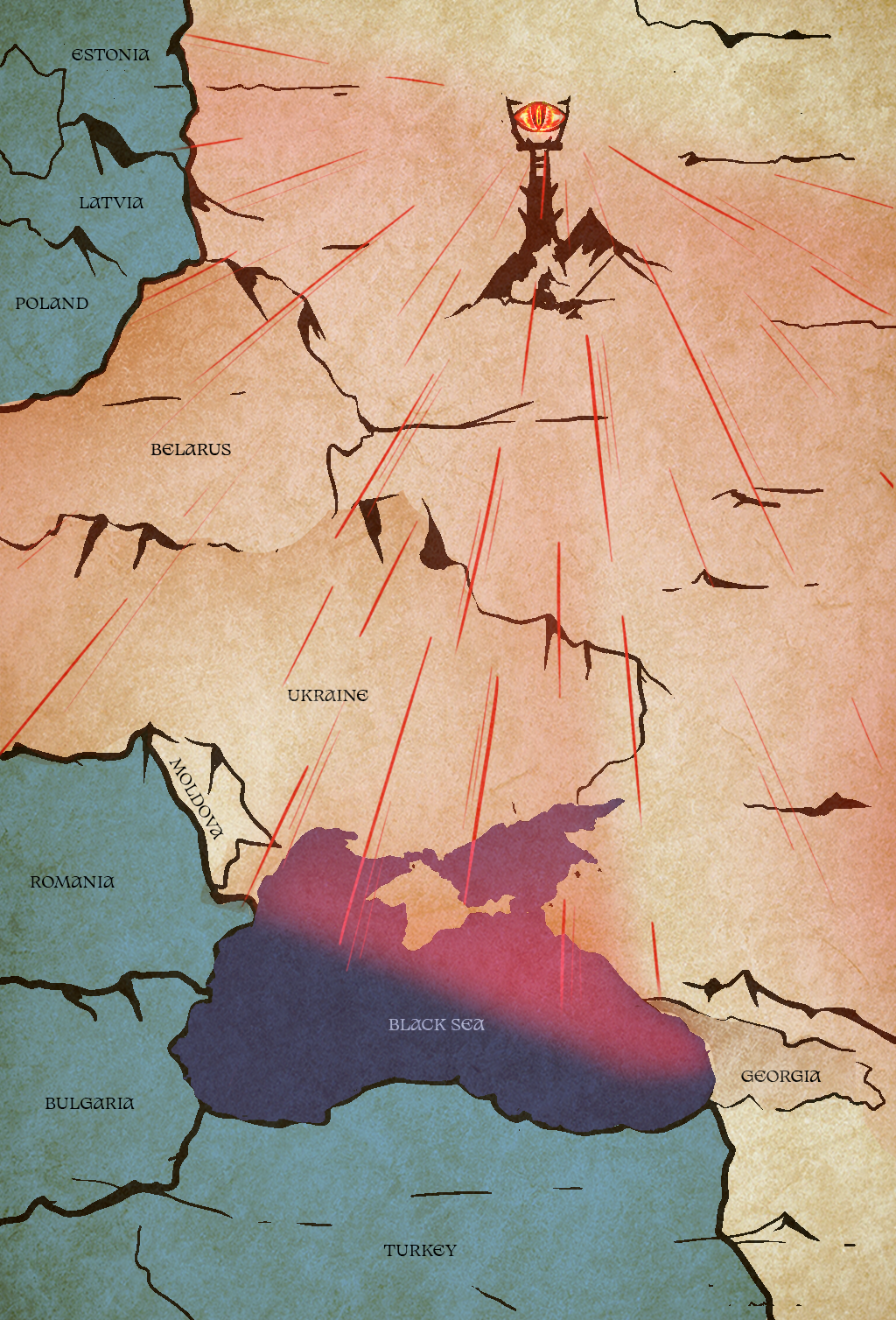

There has always been a noticeable difference in threat perceptions and security approaches towards the northern and southern parts of the eastern frontline between NATO and Russia. While the wider Baltic Sea region is firmly anchored into NATO, the southern flank is increasingly vulnerable. The strategic concept embraced by NATO in 2022 recognizes the interconnectedness of security for aspirant countries with the alliance's own security. Moreover, the new posture underscores that the strength of any alliance equals the strength of its weakest link, aiming to address imbalances between the north-eastern and south-eastern flanks by adopting a forward defense stance.

The north-east, which includes Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, and Sweden (also referred to as the Baltic-Nordic region or wider Baltic Sea region), comprises countries that are members of the EU or both NATO and the EU. This facilitates easier regional cooperation and closer focus in Brussels.

The south-east (or the wider Black Sea region), consisting of Bulgaria, Romania, Türkiye, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, exhibits more diversity in terms of membership, with Romania and Bulgaria belonging to both the EU and NATO, Türkiye being a NATO member and Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine still awaiting membership in either organization. These differences in membership contribute to diverse intra-regional perspectives and difficulties in shaping sub-regional policies in Brussels.

The countries in the south, in contrast to those in the north, navigate varied levels of relation- ships and security guarantees from NATO and the EU, guiding them to seek unique or collective regional approaches to common challenges.

The countries in the south, in contrast to those in the north, navigate varied levels of relationships and security guarantees from NATO and the EU, guiding them to seek unique or collective regional approaches to common challenges. These varied degrees of engagement restrict the potential for regional defense and security collaboration on the one hand and, on the other, complicate the consensus-building process for regional security strategies within Brussels.

Evolution of the NATO Approach

Regardless of the differences from north to south, both segments of the frontline share a commonality in the modus operandi of the EU and NATO based on the principle of avoiding escalation and provocation with Russia at all costs.

For years, the EU and NATO lacked a clear, proactive strategy for the Eastern frontline, only reacting to Russia’s aggression. Yielding initiative and constant endeavors to avoid provoking Russia had the opposite effect, weakening the West’s deterrence capabilities and emboldening Russia’s reckless hybrid strategy.

While the Baltic and Nordic countries maintained a high threat perception, the annexation of Crimea revealed that space for Russia in the north was much more restricted, whereas the Black Sea region remained vulnerable and exposed.

The analysis of the so-called Gerasimov doctrine or Russia’s coherent strategy of regaining control over the post-Soviet space and preventing NATO enlargement shows that with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Kremlin aimed at grabbing low-hanging fruit in the south with the hope of a return to its agenda in the north at the next stage.

The North appeared well positioned to capitalize on Russia’s strategic failure in Ukraine by strengthening regional security through NATO’s enlargement and enhanced defense posture. However, the security situation in the Black Sea continues to deteriorate, endangering Euro-Atlantic security due to Russia’s control of the military status quo and vital trade routes.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, NATO shifted its focus back to collective defense and protecting the territories of its member states. NATO’s posture still aims to avoid provoking Russia, maintaining a cautious approach towards opening clear membership perspectives for Ukraine and focusing its narratives on NATO not being part of the conflict as well as the defensive nature of the alliance.

NATO’s actual depiction of the eastern flank only includes member states, notably excluding Türkiye, as a significant eastern ally, as well as strategic partners and aspirants like Georgia and Ukraine. The reinforced posture involves doubling the existing multinational battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland by adding four new battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia. Multinational battlegroups provided by framework nations and contributing allies are permanently integrated into the armed forces of the host countries to defend every inch of NATO’s territory. Troops from contributing nations rotate within battlegroups, allowing deployment or rapid response from their home countries as required.

However, NATO requires a decisive and comprehensive strategy to effectively address and rectify pressing security challenges and vulnerabilities across the entire eastern frontline, encompassing allied and partner territories. A successful model tested in the Baltic Sea basin could be useful in the Black Sea region, but that would require a significant bolstering of strategic planning and operational capabilities.

Situation in the North-East

The perception of conventional security threats in the Nordic-Baltic region has remained consistently high over the past few decades. The unintended consequence of the war in Ukraine for Russia is the quick accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, a development that has reshaped the geopolitical landscape. Although consensus has been achieved regarding Finland’s accession, Sweden’s membership remains pending. The enlargement of NATO in the Nordic-Baltic theatre is poised to bring significant shifts in the power balance between NATO and Russia. Both Finland and Sweden boast substantial military capabilities that will bolster the Alliance. With the Nordic countries possessing the largest F35 fleet outside the US, this enlargement will enhance NATO’s overall strength and provide robust military resources for addressing regional contingencies.

Despite their own security concerns, Nordic and Baltic countries have been punching above their weight to support Ukraine.

Despite their own security concerns, Nordic and Baltic countries have been punching above their weight to support Ukraine. At the same time, there is an urgent need to develop national and regional defense capabilities further. Estonia announced plans to spend 3% of its GPD on defense and security. Other countries of the region aim for similar increases, while many allies are still struggling with turning a 2% ceiling into a baseline. However, NATO’s stronger position and stance in the wider Baltic region defines the defense and security policies of the regional players.

At the 2014 Wales Summit, NATO initiated its Readiness Action Plan and Adaptation to Security, establishing eight NATO Force Integration Units (NFIUs) in various Eastern European countries. The first six NFI-Us became fully operational by the summer of 2016, with the last two achieving full operational status in 2017. A summit was held in Warsaw in 2016 in response to Russian violations of the Minsk Protocol in 2015. There, the Alliance decided to establish NATO’s forward presence (Enhanced Forward Presence – eFP) and deploy multinational battalion-size battle groups to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland by 2017.

After reassessing Russia’s threat in 2022, NATO held a Summit in Madrid. During this summit, the Alliance agreed to enforce all eFPs and expand the NATO Force Model to include more troops at high readiness, and Estonia committed to establishing a land forces division in December 2022. In 2023, a new generation of regional defense plans was approved at the Vilnius Summit. Additionally, the Alliance focused on improving the readiness, preparedness, and interoperability of NATO’s Integrated Air and Missile Defense on the eastern flank. Upon the completion of NATO enlargement in the north, Russia will experience a notable reduction in its capacity to block allied reinforcements to the Baltic states via the Suwalki gap. Moreover, Kaliningrad, once a strategic military asset, will transition into an increasingly indefensible position, exposing a critical vulnerability for Russia.

Situation in the South-East

Black Sea security first gained NATO’s attention at the Warsaw Summit in 2016 when the Alliance declared its intention to actively enhance security in the Black Sea for the first time. The Summit Declaration also emphasized the role of partner countries, including Ukraine and Georgia, and the importance of engaging them in a strategic dialogue on Black Sea security. Furthermore, during a meeting of NATO Defense Ministers in October 2016, six member states - Canada, the US, Poland, Germany, the Netherlands and Türkiye - expressed their readiness to contribute to strengthening NATO’s presence in the Black Sea region, not only at sea but also on land and in the air. In practical terms, allied measures were limited to air policing missions, joint exercises, and an assistance package for Georgia and Ukraine.

At the Brussels NATO Summit in 2018, allies decided to extend NATO’s forward presence along the Alliance’s eastern flank from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. While additional ships, planes, and troops were deployed in the north, including soldiers added to NATO’s battlegroups and fighter jets for air policing missions, the measures in the south mainly involved heightened troop readiness. In addition, the highest-readiness element of the NATO Response Force was inaugurally deployed to Romania. However, in contrast to developing defense and warfighting capabilities under the enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the north, NATO’s tailored Forward Presence (tFP) in the south only aimed at enhancing situational awareness, interoperability, and responsiveness. This is a clear example of the negative consequences of diverging security viewpoints among regional countries as well as in the EU and NATO.

Unlike previous similar documents, the NATO strategic concept adopted at the 2022 Madrid Summit acknowledged that the Black Sea region is strategically important for the Alliance. Consequently, the allies agreed to establish four more multinational battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia. In Madrid, the allies also recognized the geo-economic importance of the Black Sea region and Ukraine’s grain exports for global food security, accusing Russia of intentionally exacerbating a food crisis affecting billions of people worldwide. Later, in July 2023, at the NATO-Ukraine Council meeting, Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated that Russia bears full responsibility for its dangerous and escalatory actions in the Black Sea region and must stop weaponizing hunger and threatening the world’s most vulnerable people with food instability. Russia continues to pose substantial risks to the stability and freedom of navigation in the Black Sea region, and a solution to the problem is nowhere in sight.

Defining Factors for Black Sea Security

The current status quo across the eastern flank is largely dictated by the stance and approaches of the two vitally important stakeholders – the US and Türkiye.

The current status quo across the eastern flank is largely dictated by the stance and approaches of the two vitally important stakeholders – the US and Türkiye. The US has a visible presence and active engagement across the northern part of the eastern flank, with its troops and equipment prepositioned in Poland and vibrant military cooperation with Nordic countries. In stark contrast, a recently initiated bipartisan Black Sea Security Act only provides a set of useful ideas; however, it is obvious that the US will rely on reassurance measures more than deterrence or defense in the short to medium term. At this stage, US engagement in the southeast is limited to sporadic activities in Romania and difficult relationships with Türkiye.

Türkiye has become a factor in the north as it started to veto Sweden's and Finland's accession. According to many experts, the Turkish veto is related to its difficult relationships with the US and its failure to agree on military acquisitions that are vitally important for the country’s defense needs. Notably, Türkiye has a key to any major efforts aimed at upholding security, safety, stability, and freedom of navigation in the Black Sea region through the 1936 Montreux Convention, restricting the ability of non-Black Sea countries to maintain credible forces in the region by limiting tonnage and rotation time of their vessels.

After Sweden formally joins NATO, Russia will likely reconsider its approach towards the Baltic region and limit its appetite for the sphere of exclusive influences in the north. Accordingly, Russia will probably increase its efforts and concentrate its resources on the Black Sea region. Relocation of all its warfighting capabilities from the Western military districts toward Ukraine can be considered the first sign of such acknowledgment by Russia. Another symptom of Russia’s clear focus on achieving supremacy in the Black Sea region is its accelerated efforts to extend its influence in Georgia. In parallel with massive hybrid warfare activities, Russia also reinforces its military presence by partially relocating its Black Sea fleet to a military base in the occupied region of Abkhazia. Manipulation by extending zones of destabilization and the escalation of conflicts are Russia’s tools of last resort in its pursuit of spheres of its exclusive influence.

Consequences for the Black Sea Region

NATO seems to be laser-focused on collective defense, preparing for high-intensity and multi-domain operations and ensuring reinforcement of any ally on short notice from north to south. While this might be good news for the Nordic-Baltic region, soon to be fully covered by Article 5 security guarantees, such an approach is hardly enough to ensure security and stability in the Black Sea region.

Full-fledged military cooperation and enlargement process in the Black Sea region is still hostage to the fear of escalation with Russia, preventing adequate measures desperately needed to ensure regional security and stability. Finland’s and Sweden’s decisions for quick membership are practical proof that only NATO membership can deter Russian aggression in the new security environment.

The absence of a cohesive Western vision regarding the ultimate resolution of the conflict in Ukraine provides Russia with a sense of optimism.

The effectiveness and the resolve of the Western response to the war in Ukraine will largely define security dynamics in the whole Euro-Atlantic area, and particularly in the Black Sea region. The absence of a cohesive Western vision regarding the ultimate resolution of the conflict in Ukraine provides Russia with a sense of optimism. Russia anticipates that sustaining the conflict will result in Western fatigue, leading to dwindling support for Ukraine, a relaxation of sanctions, and, ultimately, a degradation of Ukraine’s capacity to resist.

If Russia manages to maintain occupation of some parts of Ukraine, it will be able to maintain its primacy in the whole Black Sea region. In this scenario the entire Black Sea region could become hostage to Russia’s destabilizing tactics. Consequently, Moldova and Georgia would continue to grapple with the destabilizing consequences of Russian control over occupied territories, hindering both their internal progress and external prospects.

Way Ahead

Any successful Western strategy in the Black Sea must include security assurances to Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia.

There is a successful model of including partners in regional security considerations in the Baltic region. The leadership of the US in the process is indispensable both for forging unified regional security views among regional countries and for stimulating bold decisions in Brussels. The Black Sea Security Act could serve as a good starting point; however, actions on the ground aimed at pinpointing the strong US presence in the region through prepositioning the troops and equipment and increased visibility measures are still needed and long overdue. Strong military cooperation taking into account the real defense needs of the countries in the region under similar terms as in the Nordic- Baltic region will be vital.

A crucial element in deterring Russia from exacerbating the instability in the Black Sea region is the establishment of a clear roadmap for Ukraine and Georgia’s accession to NATO. It is imperative that NATO take substantive steps to translate the political decision made in Bucharest sixteen years ago into actionable measures. To achieve this, NATO must ensure that unresolved conflicts no longer serve as a reason for vetoing the enlargement process. This can be accomplished by extending security guarantees to the unoccupied territories of both Ukraine and Georgia. Such a proactive approach would send a resounding signal to Russia, signifying NATO’s unwavering commitment to Black Sea security on par with other areas within the alliance, effectively discouraging Russia from engaging in further military aggression in its neighborhood.